Can Humans Be Replaced by Machines?

By James Fallows

The Mavericks Who Brought AI to Google, Facebook, and the World

9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation

It is as hard to understand a technological revolution while it is happening as to know what a hurricane will do while the winds are still gaining speed. Through the emergence of technologies now regarded as basic elements of modernity — electric power, the arrival of automobiles and airplanes and now the internet — people have tried, with hit-and-miss success, to assess their future impact.

The most persistent and touching error has been the ever-dashed hope that, as machines are able to do more work, human beings will be freed to do less, and will have more time for culture and contemplation. The greatest imaginative challenge seems to be foreseeing which changes will arrive sooner than expected (computers outplaying chess grandmasters), and which will be surprisingly slow (flying cars). The tech-world saying is that people chronically overestimate what technology can do in a year, and underestimate what it can do in a decade and beyond.

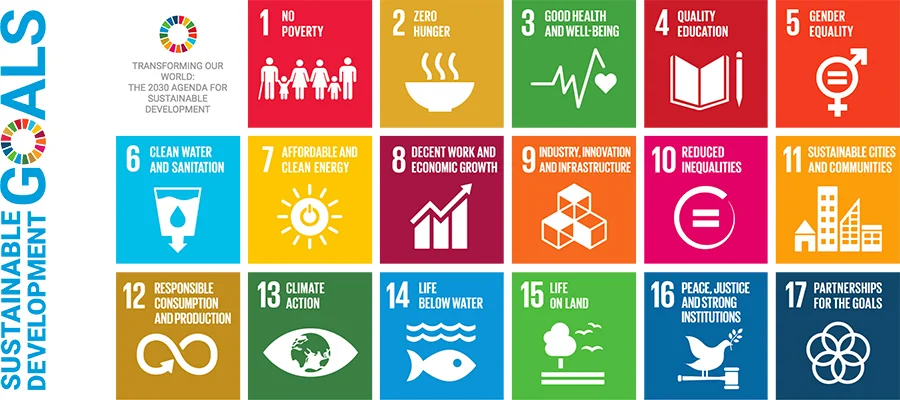

So it inevitably goes with one of this moment’s revolutions, the combination of ever-higher computing speed and vastly more-voluminous data that together are the foundations of artificial intelligence, or A.I. Depending on how you count, the A.I. revolution began about 60 years ago, dating to the dawn of the computer age and a concept called the “Perceptron” — or has just barely begun. Its implications range from utilities already routinized into daily life (like real-time updates on traffic flow), to ominous steps toward “1984”-style perpetual-surveillance states (like China’s facial recognition system, which within one second can match a name to a photo of any person within the country).

Looking back, it’s easy to recognize the damage done by waiting too long to face important choices about technology — or leaving those choices to whatever a private interest might find profitable. These go from the role of the automobile in creating America’s sprawl-suburb landscape to the role of Facebook and other companies in fostering the disinformation society.

“Genius Makers” and “Futureproof,” both by experienced technology reporters now at The New York Times, are part of a rapidly growing literature attempting to make sense of the A.I. hurricane we are living through. These are very different kinds of books — Cade Metz’s is mainly reportorial, about how we got here; Kevin Roose’s is a casual-toned but carefully constructed set of guidelines about where individuals and societies should go next. But each valuably suggests a framework for the right questions to ask now about A.I. and its use.

“Genius Makers” is about the people who have built the A.I. world — scientists, engineers, linguists, gamers — more than about the technology itself, or its good and bad effects. The fundamental technical debates and discoveries on which A.I. is based are a background to the individual profiles and corporate-drama scenes Metz presents. The longest running, most consequential debate is between proponents of two different approaches to increasing computerized “intelligence,” which can be oversimplified as “thinking like a person” versus “thinking like a machine.”

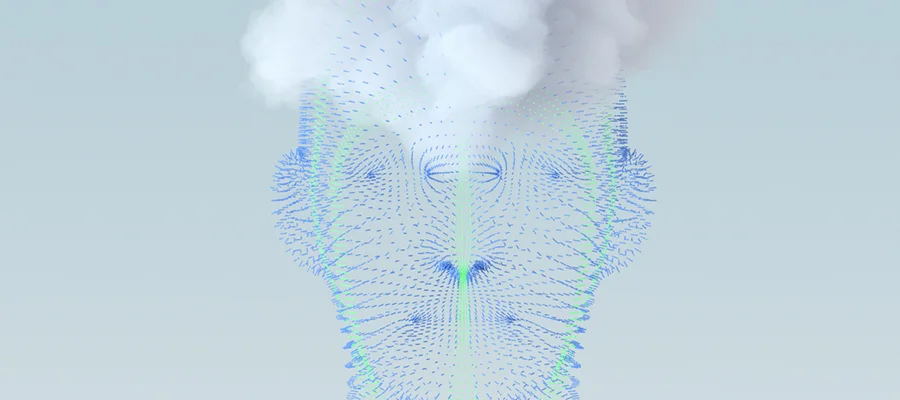

The first boils down to using “neural networks” — the neurons in this case being computer circuits — that are designed to conduct endless trial-and-error experiments and improve their accuracy as they match their conclusions against real-world data. The second boils down to equipping a computer with detailed sets of rules — rules of syntax and semantics for language translation, rules of syndrome-pattern for medical diagnoses. Much of Metz’s story runs from excitement for neural networks in the early 1960s, to an “A.I. winter” in the 1970s, when that era’s computers proved too limited to do the job, to a recent revival of a neural-network approach toward “deep learning,” which is essentially the result of the faster and more complex self-correction of today’s enormously capable machines.

Metz tells the story of more than a dozen of the world’s A.I. pioneers, of whom two come across most vividly. One is Geoffrey Hinton, an English-born computer scientist now in his mid-70s, who is introduced in the prologue as “The Man Who Didn’t Sit Down.” Because of a back condition, Hinton finds it excruciating to sit in a chair — and he has not done so since 2005. Instead he spends his waking hours standing, walking or lying down. This means, among other things, that he cannot take commercial airplane flights. In one crucial scene of Metz’s tale he is placed on a makeshift bed on the floor of a Gulfstream, and then strapped down for the flight across the Atlantic to an A.I. meeting in London.

The other most prominent figure in Metz’s book is Demis Hassabis, who grew up in London and is now in his mid-40s. He is a former chess prodigy and electronic-games entrepreneur and designer who founded a company called DeepMind, now a leading force in the quest for the grail of A.G.I., or artificial general intelligence.

“Superintelligence was possible and he believed it could be dangerous, but he also believed it was still many years away,” Metz writes of Hassabis. “‘We need to use the downtime, when things are calm, to prepare for when things get serious in the decades to come,’ he has said. ‘The time we have now is valuable, and we need to make use of it.’”

Making use of that time is the entire theme of “Futureproof.” Roose’s book has two sections: “The Machines,” about the surprising potential and equally surprising limits of automated intelligence, and “The Rules,” which offers nine maxims for how people and organizations can best respond. In structure the book might look like a familiar, business-oriented “Secrets of Success” tract. But it is actually a concise, insightful and sophisticated guide to maintaining humane values in an age of new machines.

In the book’s first section, Roose lays out distinctions between jobs and industries in which A.I. is likely to dominate, and those where it still disappoints. Computers are unmatchable in speed and complexity within known boundaries — the rules of chess, even the way points an airplane must follow through the sky. (Today’s airlines can use A.I. guidance to “autoland” without a pilot, whereas today’s cars can’t safely “autodrive” down your street, in part because no pedestrian is going to lurch into a plane’s descent path.) But the more fluid the setting, the greater the difficulties. “Most A.I. is built to solve a single problem, and fails when you ask it to do something else,” he writes. “And so far, A.I. has fared poorly at what is called ‘transfer learning’ — using information gained while solving one problem to do something else.”

Roose links this technological transformation to the many others that societies have undergone. Nearly all have eventually made humanity richer overall — in the long run. But, he writes, “we don’t live in the aggregate or over the long term. We experience major economic shifts as individuals with finite careers and life spans.”

“Futureproof” offers suggestions for individual pursuits and for social policy. But the most eloquent parts of the book come when Roose moves from preserving livelihoods to protecting basic humanity.

Social-media algorithms, he points out, are ever more precisely honed to attract and hold your attention. Click on the next video, scroll to the next tweet. Thus technology becomes humanity’s master, rather than the reverse. “There are established ways to train our brains to better guard our attention,” writes Roose — who, it is worth noting, is a millennial-era writer who specializes in digital technology. “For me, the best attention-guarding ritual of all is reading — sitting down to read physical, printed books for long stretches of time, with my phone sequestered somewhere far away.”

Technology’s effects are driven by technology itself, but even more by human choice. Roose warns against treating “technological change as a disembodied natural force that simply happens to us, like gravity or thermodynamics.” Instead we all should realize that “none of this is predetermined. … Regulators, not robots, decide what limits to place on emerging technologies like facial recognition and targeted digital advertising.” The message from both of these books is that the sky is not falling — but it could. There is time to make a choice.

James Fallows is a staff writer for The Atlantic. An HBO documentary based on his book “Our Towns,” co-authored with his wife, Deborah Fallows, will air April 13.

GENIUS MAKERS

The Mavericks Who Brought AI to Google, Facebook, and the World

By Cade Metz

384 pp. Dutton. $28.

FUTUREPROOF

9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation

By Kevin Roose

256 pp. Random House. $27.

Source: NYT

Looking for a custom web design? Then Contact the website designers at The ÂN in Vietnam via (+84).326.418.478 (phone, zalo, viber) or schedule a consultation.

Other useful information: