5 Questions Boards Should Be Asking About Digital Transformation

by Celia Huber, Alex Sukharevsky, and Rodney Zemmel

Summary. Digital transformation is increasing the scope of boards’ mandates, opening up new fronts for risk and competition. Asking the following five questions will ensure that even non-digital directors are focused on the most important challenges: 1) Does the board understand the implications of digital and technology well enough to provide valuable guidance? 2) Is the digital transformation fundamentally changing how the business (and sector) creates value? 3) How does the board know if the digital transformation is working? 4) Does the board have a sufficiently expansive view of talent? 5) Does the board have a clear view of emerging threats?

The CEO of a large retail company recently brought a $500 million digital-transformation-investment plan to his board. The board reviewed the proposal, but after asking a number of questions, they were unable to evaluate it. Was it too costly? Was it aiming too low? Was it focused on the right priorities? One board member admitted he just didn’t know.

Similar scenes have been playing out in boardrooms around the world for years. “I hear lots of digital buzzwords, but I’m not sure how to deal with it,” as the chairman of a different board put it. “I know digital is important, but how do we capture the value?”

Even before the pandemic, 92 percent of companies surveyed by McKinsey believed their business models would have to change given rates of digitalization at the time. Covid-19 has only accelerated that timeline, with estimates indicating we’ve moved three to four years forward in digital adoption in a matter of months. Digital transformation has become a matter of corporate survival and a top priority for boards.

While many board members have told us they know that digital is essential to keeping current business models viable while developing new revenue streams, they struggle to see how they can best add value. The complexity of technology and the speed of digital can make board members feel like they’re always playing catchup.

Discussions with dozens of board members reveal how digital transformation is increasing the scope of the board’s mandate, opening up new fronts for risk and competition. Rising to the challenge doesn’t mean completely reinventing the board model, but it does require a thoughtful recalibration of where to focus directors’ energies. Asking the following five questions will ensure that boards are focused on the most important digital challenges. While some of these questions are more strategic, and others more operational, boards that address all of them can help push companies to achieve the digital transformations essential to today’s competitive advantage.

1. Does the board understand the implications of digital and technology well enough to provide valuable guidance?

Building up the board’s digital aptitude isn’t about turning directors into proficient technologists. Rather, the goal is for the board to understand the implications of technology and digital on the business and sources of revenue. Take artificial intelligence (AI), for instance. When thoughtfully applied, it can enable a huge leap over standard approaches in terms of delivery speeds, costs, and quality – often by a factor of 10. This allows companies to test new markets, products, and business models at much greater speeds, and at lower costs. Adding in other technology trends at varying degrees of maturity and applicability — such as quantum computing, distributed IT infrastructures, and process automation and virtualization — means boards have their work cut out for them in navigating potential impacts on the business.

Bringing on tech experts, setting up advisory groups, or visiting tech companies to see how they work are useful but ultimately insufficient steps, because they often reflect a board-level view that digital is merely a sidebar to the core business.

Two practices go further. First, boards can take a more strategic view when bringing on new directors. Leading boards dig into their target hire’s actual experience in digital transformations and rigorously review how well it fits with the company’s digital strategy. For example, one retailer looking to speed up its digital enablement brought an executive onto the board who’d recently done exactly that for another retailer, upending an industry in the process. Another retailer looking to better integrate the digital logistics of its e-commerce and brick-and-mortar operations targeted someone with exactly that top-management experience and expertise.

Another best practice is to put board members through intensive training programs led by external faculty or top technologists from the company that focus on the business implications of key technologies and methodologies. We spoke to 75 board members who completed this kind of immersive training and found that more than 50% insisted on making digital transformation the top agenda item for the business. The point of this kind of training isn’t to build up digital skills but to shift mindsets: Coming out of a learning session, one board member said that only at that moment did he realize that digital transformation wasn’t a chief information officer (CIO) or chief technology officer (CTO) responsibility, but a CEO one.

2. Is the digital transformation fundamentally changing how the business (and sector) creates value?

One of the board’s main obligations is to push company leadership on business models and value creation and capture. In the context of a digital transformation, there are three vectors of value: scale (is the new value big enough?), source (where is the value coming from?), and scope (are we thinking long term enough?).

- Scale: One director who sits on multiple boards told us, “In almost every case, the digital aspirations of the business aren’t bold enough.” Businesses often settle on aspirations that are based on last year’s performance plus 5 or 10%. But the pandemic has shown that businesses can take huge leaps when pressed. Our power-curve research emphasizes that bold moves are required to jump into the top quintile of performance. As a rule of thumb, digital initiatives should change more than 20% of operating profits — even as revenue and profit-growth targets continue to rise. That means conversations at the board level, and between the board and management, must tackle the ways digital will change the technology model, operating model, or business model of the company — or even its industry.

- Source: Too many board conversations default to how technology can improve efficiency and cut costs. Efficiency can indeed generate meaningful savings that can help meet the ongoing investment needs of a digital transformation. But digital is a game changer when it comes to generating new sources of revenue. Recent McKinsey research into cloud economics, for example, has shown that as much as 75% of the $1 trillion at stake in cloud will come from business innovation. Boards need to push management to develop a granular understanding the company’s real sources of competitive advantage and how the transformation leverages these advantages to deliver significant new sources of revenue.

- Scope: Investment horizons at many companies tend to be too focused on the short term. Amazon, in contrast, has had a seven-year horizon for its investments. For many companies facing short-term pressures, this long-term focus can be particularly challenging (especially in capital markets) since digital transformations cost a lot while promising cash-flow and revenue payoffs that won’t arrive till much later. By developing a clear view of long-term value, however, the board can press the business to make the multiyear operating-expenditure and capital-expenditure spend that’s necessary to capture that value.

A long-term view of where the value is heading is crucial to getting digital transformations right. Too often companies invest for competitive advantage and wind up with table stakes instead, as everyone else in the industry has been making the same investments. Distribution centers, for example, now require continued investment rounds to modernize management systems, develop automation capabilities, share data with suppliers and customers in real time, and more. One retail company had to replatform frequently to compete in e-commerce, mobile, and logistics.

The faster pace of investment means boards must press hard on management assumptions, pushing top executives to articulate how they see the industry evolving now and in the future. The executive team’s analysis must account for the shifts digital brings to the underlying supply-and-demand elements of an industry, as evolving ecosystems and hyperscale platforms shake up traditional value chains, disintermediating and often substituting for the offerings of traditional competitors. For example, successful ecosystems can tap into huge pools of value by dominating customer interfaces and controlling points such as search, advertising, and messaging. The board’s role is to push the top team to peer around corners and take into account the falling barriers across industries and sectors. Only then can the board feel confident that the proposed investment will help the business jump up the curve, rather than merely stay mired in the middle of the pack.

3. How does the board know if the digital transformation is working?

Digital transformations are complex programs with dozens or even hundreds of initiatives. This can generate a soothing level of activity, but it tells you very little about whether your digital transformation is on track.

To get past the noise, boards can start with a hard-nosed assessment of the strategy and road map. “You better make sure that there is a common understanding of the business’ digital strategy, and that management has broken apart every part of the business model to assess where the value is,” as one board member said. Another board member insisted that the only way to have confidence in the strategy and road map is to have it independently vetted.

The board should work with management to ensure that the business is focusing its digital-transformation efforts on the two or three domains that create the most value for the company. This focus helps avoid a number of persistent failure modes, including spreading resources thinly across multiple initiatives or focusing on a handful of disconnected experiments that can’t scale.

When tracking progress against the strategy and road map, boards should focus on two sets of metrics. The first tracks outcomes and important leading indicators tied to value (for example, customer fulfillment in e-commerce, or reduced time to first quote in insurance). As obvious as this may sound, many companies do not track ROI on their digital and technology investments or cash flow — and if they do, it often trails too far after the fact to be of real-time use. Part of measuring ROI is to establish baselines so there’s a starting point against which to track progress — something else that is also surprisingly rare and which boards can help establish.

The other set of metrics surfaces progress in the guts of the transformation itself. These metrics address changes in behaviors and processes deep in the organization. One key metric is the speed with which new ideas are translated into frontline tools. Another is the percentage of talent that’s actually working in agile teams where true change occurs. One consumer goods company tracks how many prices put into the system were AI-driven, rather than coming from the traditional route of middle-management expertise. Another board at a consumer goods company has a digital-maturity index to track how many processes have been automated, which is then benchmarked against competitors. “If you focus on the transformation, the digital part will take care of itself because digital is the only way to make the transformation happen,” as one board member told us.

4. Does the board have a sufficiently expansive view of talent?

The digital-talent discussion at the board level is often limited to expressing the need to hire more executives who are digital natives or people from consumer-facing companies that might be further along on their digital journeys. This is only part of the story. Given the scope of change required across the entire business, boards must develop an expansive view and pressure test the talent road map as much as they might the technology or digital-transformation road map.

It goes without saying that any new top-executive hire (including CEO succession candidates) must have good baseline knowledge of technology and digital. When it comes to digital transformations, however, executive hires aren’t always the most important ones. In digital companies, it’s often the data engineers, product managers, and scrum coaches — among many others — who form the backbone of the business. A McKinsey analysis shows, for example, that top engineers can be 10 times more productive than their more junior peers. Boards shouldn’t be involved at the individual hiring level, of course, but they do need to engage with senior leadership on progress made in developing this talent bench of digital expertise.

Tracking the progress of a company’s talent also extends to building up the business’ “learning” muscle. Boards can help test whether upskilling programs actually create digital capabilities across all key businesses and functions — especially in traditional IT, digital, analytics, and data. Specific questions, such as which capabilities are being bolstered and how, can help the board stay on top of talent development. As businesses ramp up their talent engine, the board can be especially helpful by helping management focus on talent needs six to 12 months in the future.

5. Does the board have a clear view of emerging threats?

Digital expands companies’ competitive footprint by blurring traditional sector boundaries. While this creates new opportunities for companies to participate in emerging ecosystems, it also generates a more complex set of threats to assess.

On the risk side, boards generally have a clear understanding of the importance of cybersecurity. Many have a framework, vetted by third parties, to help evaluate cyber risk. Digital, however, opens new and different pools of risk. Regulations about privacy grab headlines, but local compliance or national security laws, for example, have introduced unforeseen risks to businesses when their servers are located in those corresponding locations.

Keeping track of competitive threats poses similar challenges. On the one hand, there is the sheer volume of new businesses and technologies that burst onto the scene, often seemingly from nowhere. On the other hand, there’s the threat potential of established businesses operating in brand-new sectors: Think about e-commerce businesses getting into data management, tech companies moving into banking, or retailers into logistics.

Boards can help address these issues by pressing executive teams to be more externally oriented, to take the “outside view” by looking for analogs rather than direct competitors, and to inject more creativity and rigor into scenario-planning exercises. Some hedge funds, in fact, are turning to AI- and machine learning–driven analyses to provide views of the companies they invest in from the outside in, to better understand trends and their implications and to provide more sophisticated scenario plans. That can help address one board member’s concern that boards often just don’t have enough time to really pressure test strategies: “The board’s best value is asking the ‘what if’ or ‘Have you thought about …’ questions. But there’s just never enough time to dig in.”

“Digital is what we’re going to be doing for the rest of our lives,” as one executive is fond of saying. The urgency and longevity that underlie that statement make supporting a successful digital transformation job number one for boards. As the pressures and complexities of digital increase, boards have a key role to play in guiding their institutions through successful, long-term digital transformations.

The authors wish to thank Alexander Gromov for his contributions to this article.

Celia Huber is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office.

Alex Sukharevsky is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Moscow office.

Rodney Zemmel is a senior partner in McKinsey’s New York office.

Source: Harvard Business Review

Looking for a custom web design? Then Contact the website designers at The ÂN in Vietnam via (+84).326.418.478 (phone, zalo, viber) or schedule a consultation.

Other useful information:

Others article

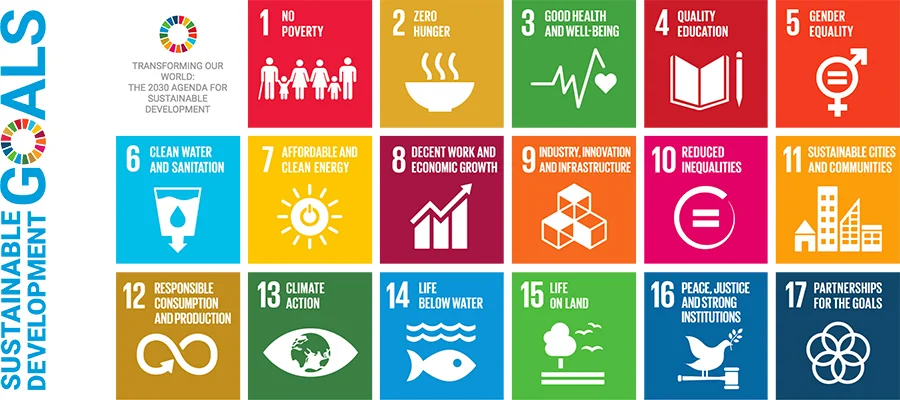

17 Sustainable Development Goals of United Nations

The SDGs build on decades of work by countries and the UN, including the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs ...

A Technology Partner Can Help Midsize Businesses Accelerate Digital Transformation

Never let a crisis go to waste. Many organizations see the pandemic not as a global catastrophe but as a rare opportunity to ...